Driving

When I drive — and especially when I do so with a spirit to wander — I’m brought to perspectives I’d not thought of at all. And those insights I simply happen upon are the most illuminating. Outside of co-ordinates, my moral imagination expands. It’s why floating across undulating ribbons of rural roads on the sultriest of summer days opens my mind and heart in ways that few things ever have.

Vulnerable

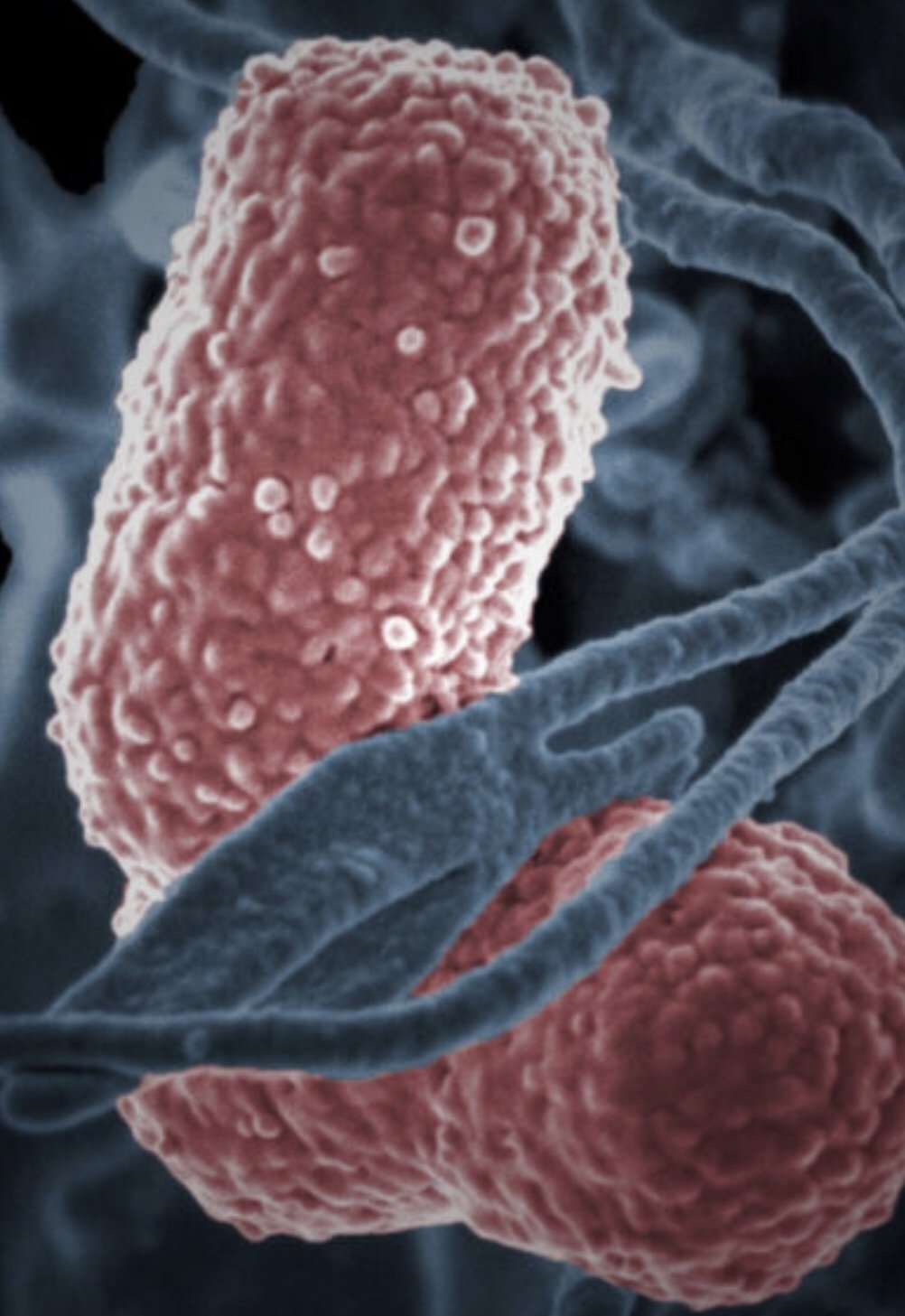

From the outset of the Trump administration, bird flu, or H5N1 avian influenza, has flown rather conspicuously — and in fact quite mysteriously — under the radar. So much so that this week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced the end of its emergency response to bird flu, citing the lack of reported human cases. Updates, previously issued weekly, will now arrive monthly. But something isn’t adding up.

Postpone

In no setting, perhaps, is this more evident than in a hospital. There, the stretches of borrowed time are laid their most plain and bare. After I pore over a screen of lab values and vital signs bolded and in red — aberrations from faltering organs — and amid tangles of tubes and the whir of life-sustaining machines, before their illness comes to claim them, a patient may express a circumstance they hope will come to pass.

Aid

But if foreign assistance is viewed for its collective benefit — to security interests, humanitarian values, and public health — it is best to understand it, perhaps, as a collective obligation. What, among the world’s nations, it once aspired to be. More importantly, what they must see it as now. No country, or single entity, can fill the gaping void left by the $44 billion enterprise that was once USAID. But the rest of the world’s wealthy nations must work together to take its place.

Prevention

It means looking not at a virus for answers — but to ourselves. Environmental and agricultural reforms to protect us from a virus that moves from one species to the next, looming over us the possibility of a pandemic, mean asking why, as people, we desire the things we do, and what a world from which we take so much from will eventually return to us.

Conflict

Pinpointing how someone becomes sick involves a careful examination of their life’s circumstances. Overcrowded environments, poor living conditions, economic insecurity, malnutrition, and limited health care infrastructure all, in some form or other, contribute to the spread of TB and other diseases. That much we know. While I had simply accepted many of these elements as hard realities of a life lived on the margins, I now find myself considering how they are intensified by a factor I had always thought outside of my grasp: warfare.

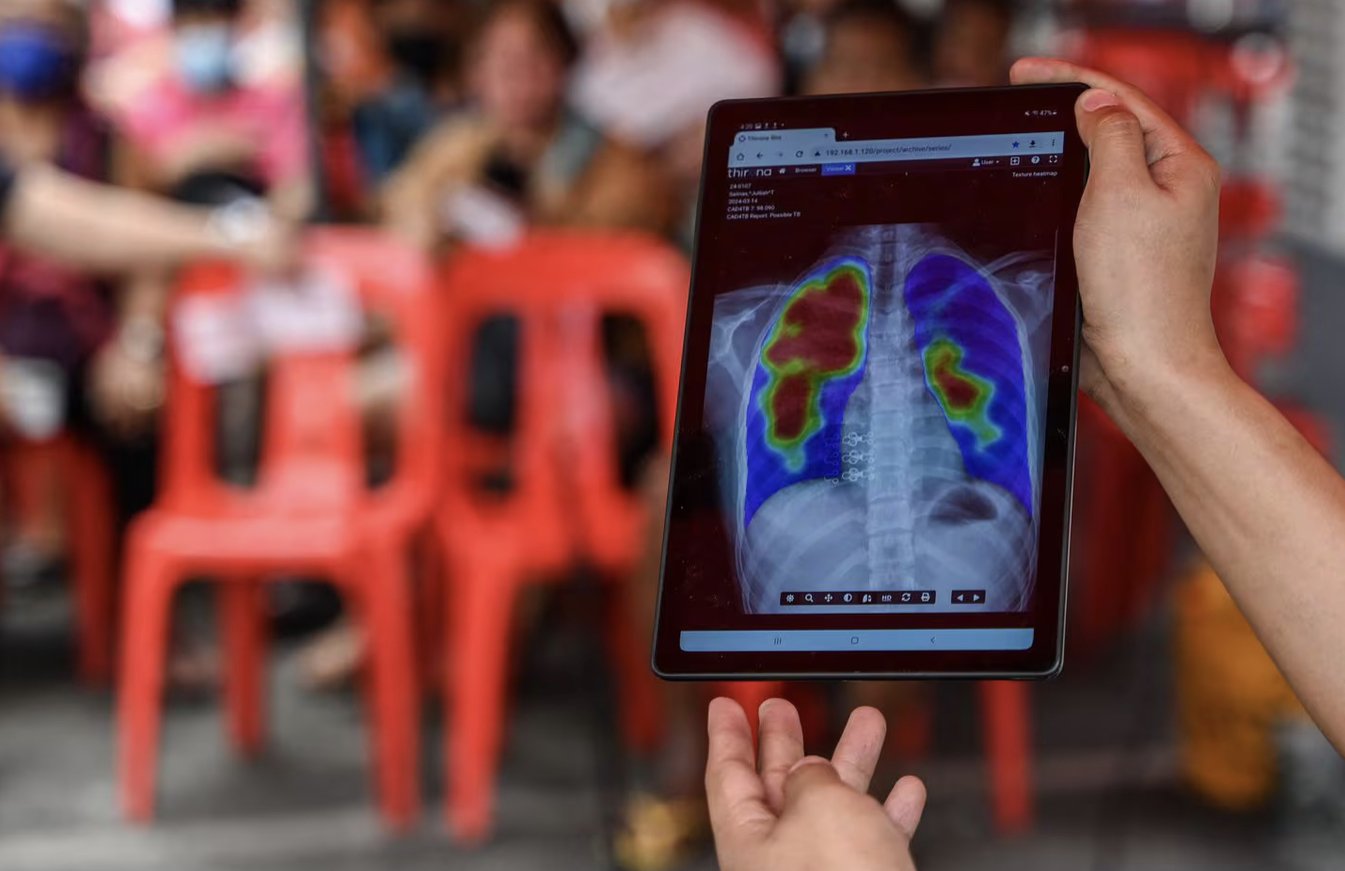

Human

I often think about what gives meaning to the help we offer patients, how that might be shaped by the precision and calculations of a looming revolution from a novel technology, or by greater investments into the social safety nets that undergird them. But, in the end, I come to the same the conclusion: that neither is of any use without the uniquely personal connections that sustain us.

Neglect

Nevertheless, many of my TB patients do live hardscrabble lives, making it harder for them to get diagnosed and access treatment. They might live in overcrowded shelters or have been incarcerated at some point. Nearly all of them are society’s marginalized, and that is where the disease finds them — at the margins.

Understanding

The health needs of the unhoused cannot be fixed with a pill. They need a more comprehensive type of healing. For doctors, whose emotional stores are still drained from the maelstrom of the last few pandemic years, this means opening our hearts and minds to our patients’ experiences. When we do that, we not only fight against the stigma attached to our patients but directly improve their health.

Rural

A connection to a rural identity could be bought with incentives, or it could be learned. Or, I realized, just as importantly, it could be lived through simple and heartfelt things: a teary “thank you,” a firm handshake, or the question, over and again, from patients of your plans to stay.

Forests

Over the years, however, my outlook shifted. As the neighborhood grew, and as each autumn wrestled the canopy of gold and crimson to the ground, exposing a sinewy understory, that humble patch of trees stayed. It held a certain magic: of permanence. I imagine when most people think of forests they summon a similar sense of everlastingness — the ability to endure a world in flux.

Renewal

What made our interaction possible, I later thought, was a remarkable program called PEPFAR. In the early 2000s, therapies for HIV were widely available in Western countries but scarce in the developing world — in places like Botswana, one-third of the adult population was infected. Millions of people were dying from AIDS.

Language

When I comfort a family after a patients’ death, I often say that they are never truly lost. People remain embodied in things: like their wedding band that slides over the next generation’s finger, or their woolen quilt that drapes the end of another bed. But for me, my grandfather, who died in 2020, remains vividly alive through language. His memory is conjured when I hear Punjabi – a language I myself could never speak.

Healing

My limbs grow heavy and my body sinks into the floor. Releasing the tension sets something free. It occurs to me that I have spent so much time over the course of the pandemic disoriented — in my thoughts, my worries, my contemplations, my ruminations. For a moment, it seems as if I’ve forced these all away.

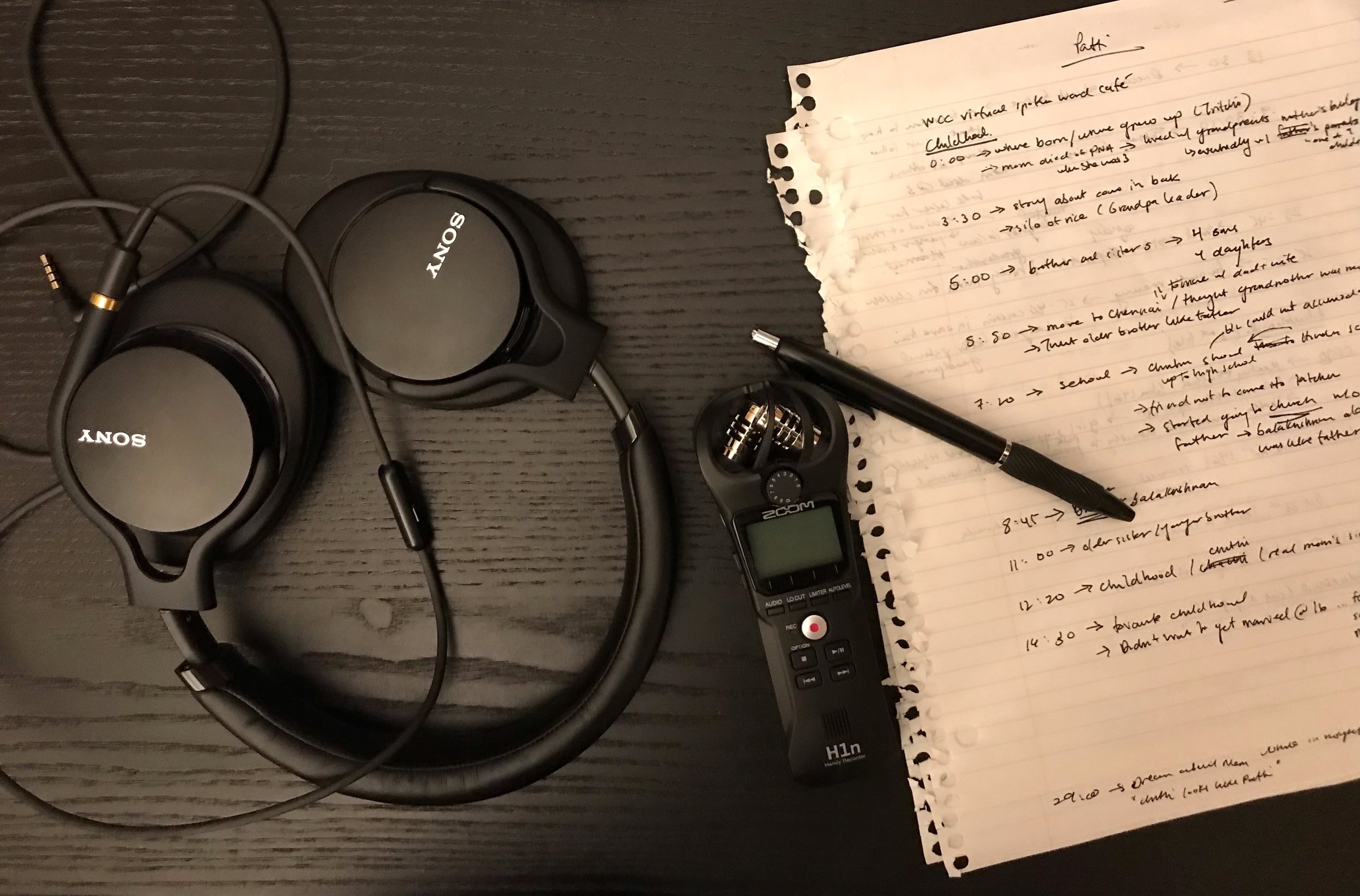

Legacy

When I play the recording for their loved ones, I witness how these little parts of my patient remain alive with them. How in speaking to those they've left, they wrap themselves around them. Stabilize them. Grieve with them. This precious bit of preservation comes to a head with a question I must ask. And one that nearly breaks me.